Sierra Smith

Ph.D. Candidate

I am on the 2025–2026 job market!

I'm currently completing my Ph.D. at Michigan State University and am primarily seeking teaching-focused faculty positions

at institutions that value high-quality undergraduate instruction and student engagement.

Find my research projects, teaching samples, and info about me by scrolling below ↓

Research Projects

When the Storm Breaks (Expectations): Reference Dependence and Demand for Flood Insurance [JMP]

[PAPER]

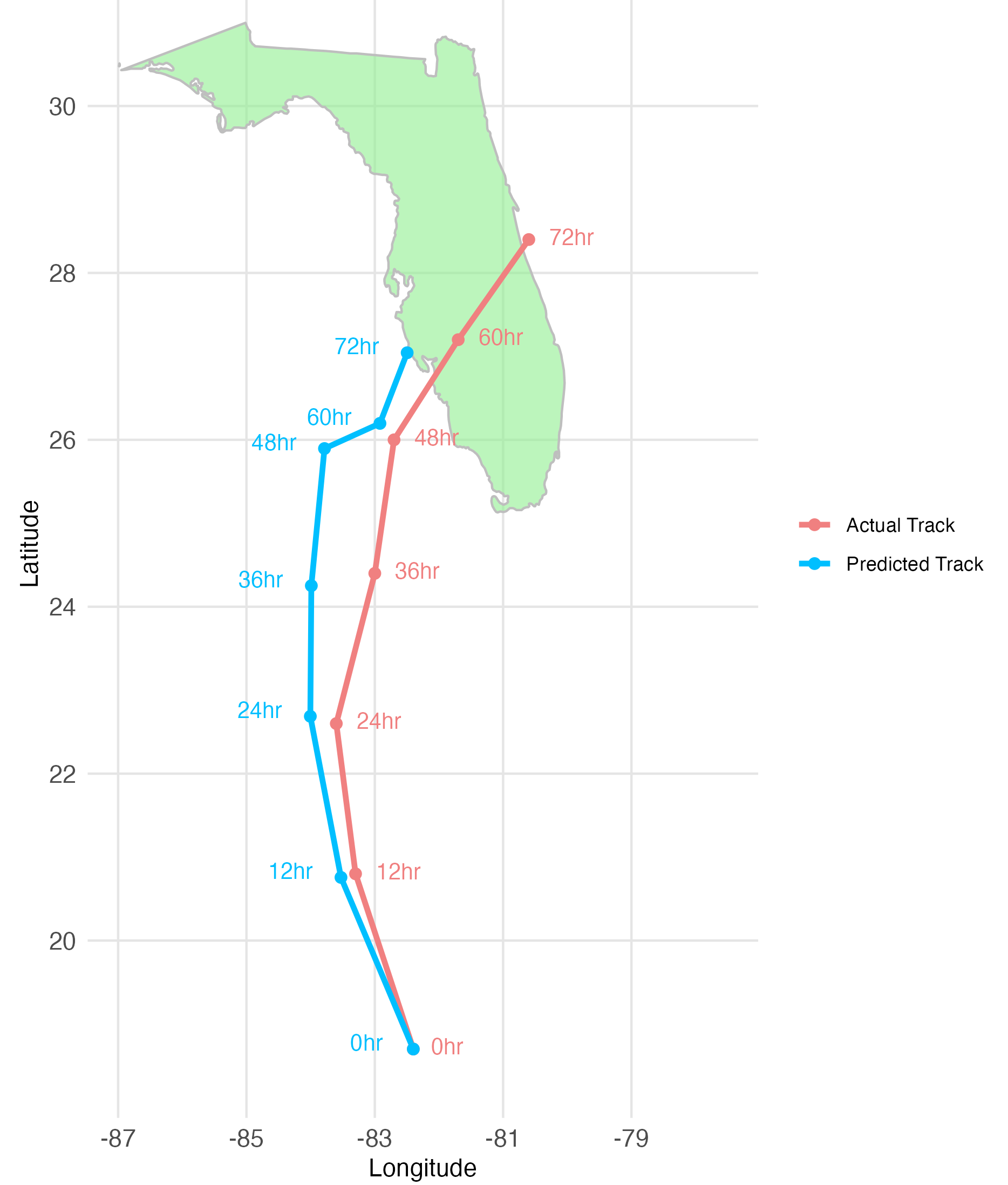

Households in hurricane-prone areas face rare but potentially devastating losses, yet flood insurance coverage remains low and unstable. This paper links hurricane forecasts to flood insurance uptake, introducing forecast errors as novel, exogenous reference points for household expectations. Using administrative records of NFIP policies in Florida merged with storm forecasts, I show that deviations between predicted and realized storm outcomes generate strong behavioral asymmetries: unanticipated impacts (“false misses”) drive large increases in demand, often exceeding the response to correctly predicted strikes (“true hits”), while predicted threats that fail to materialize (“false hits”) reduce uptake, suggesting that false alarms erode perceived risk. These patterns cannot be explained by actuarial risk alone and are consistent with reference-dependent preferences and loss aversion. Salience further amplifies these dynamics, as recent storms and hurricane-classified systems elicit the strongest responses, while near-miss “close calls” often depress demand. Together, the findings demonstrate that household insurance decisions are shaped as much by the psychological impact of forecast errors as by objective risk, with implications for forecast communication, policy timing, and disaster preparedness.

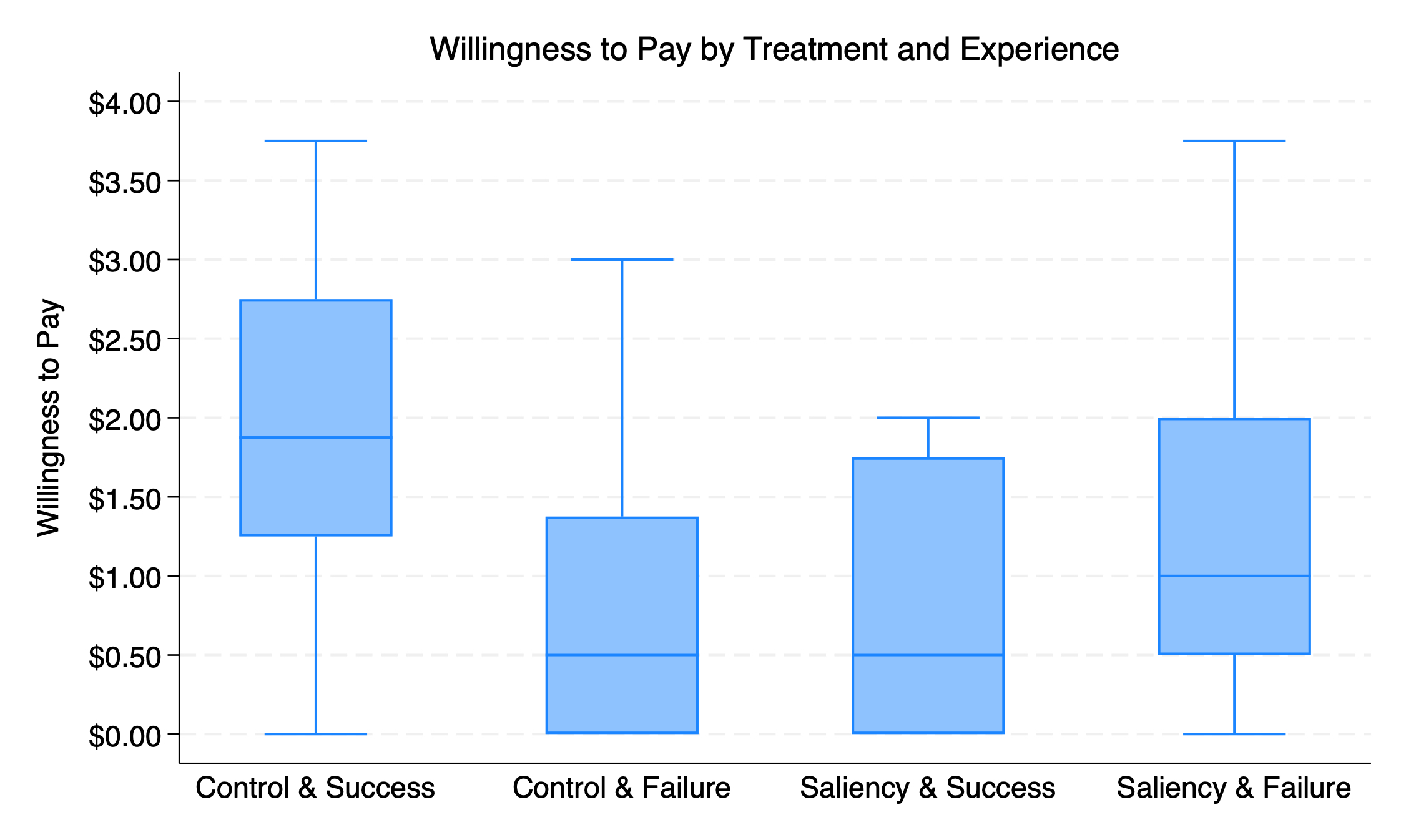

The Missing Piece: Experimental Evidence on Salience and Insurance

This paper provides experimental evidence on how salience and firsthand experience interact to shape insurance demand. Using a controlled real-effort task with certain risk, I independently manipulate the salience of potential losses and observe naturally occurring variation in prior experience. Contrary to standard theoretical predictions, both the salience enhancements and prior exposure to loss reduce willingness to pay (WTP) for insurance on average. However, when salience and negative experience coincide, WTP increases sharply, revealing strong interactive effects. This nonlinear response suggests that salience amplifies the influence of adverse outcomes but suppresses demand when recent experience is reassuring. The results point to a behavioral framework in which attention, reference points, and recent outcomes jointly determine the perceived need for protection. These findings challenge the predictions of expected-utility theory and highlight the importance of attentional signals in shaping insurance behavior.

(data collection is currently underway)

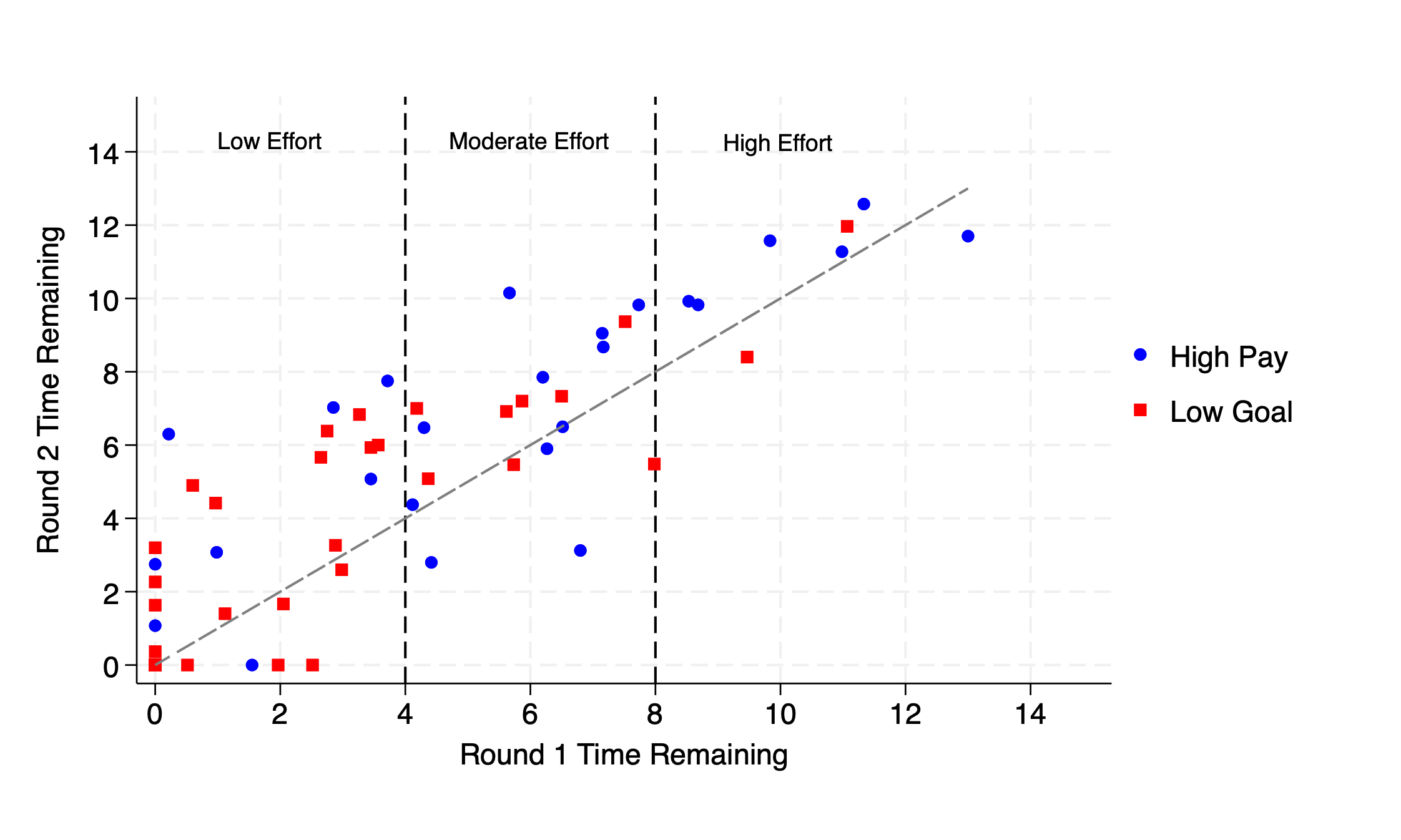

Building Effort: Reference Points and Productivity in a LEGO Task

This paper examines how reference points influence effort provision through a real-effort laboratory

experiment. In the first round, participants are asked to assemble 15 LEGO figures within 25 minutes and are compensated based on the number of minutes remaining upon completion.

In a second round, participants are randomly assigned to one of two treatments. In Treatment 1, the required output is reduced to 10 figures, with the same per-minute reward.

In Treatment 2, the original 15-figure target is retained, but participants receive a $0.75 reward per minute saved. By independently manipulating performance expectations

and pay, the design identifies whether a downward shift in the performance goal, leads to reduced effort, even when economic incentives

remain unchanged. The experiment offers a novel and transparent test of reference-dependent effort provision, isolating the behavioral effects of goal-setting from standard

monetary responses.

(data collection is currently underway)

Teaching

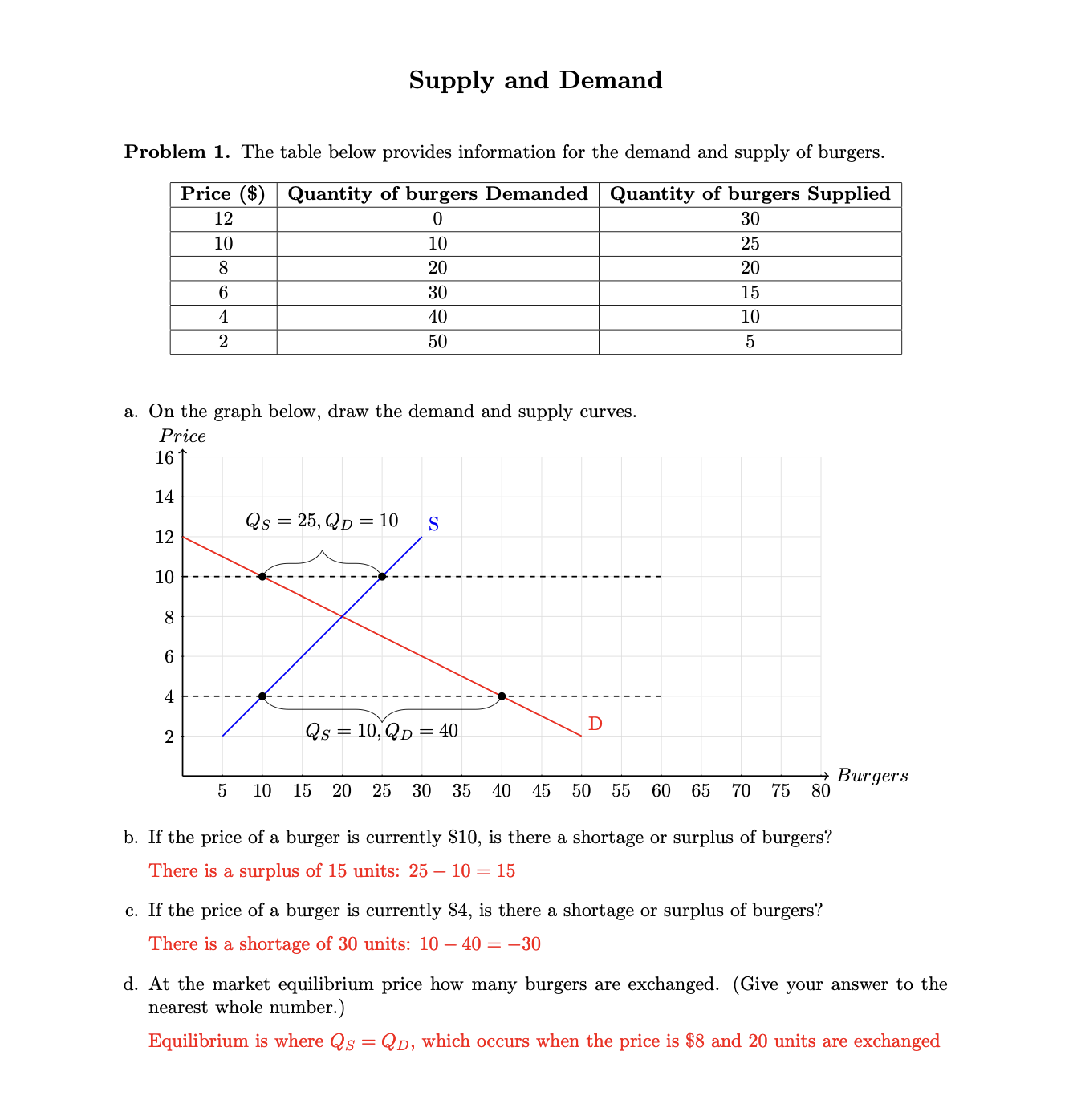

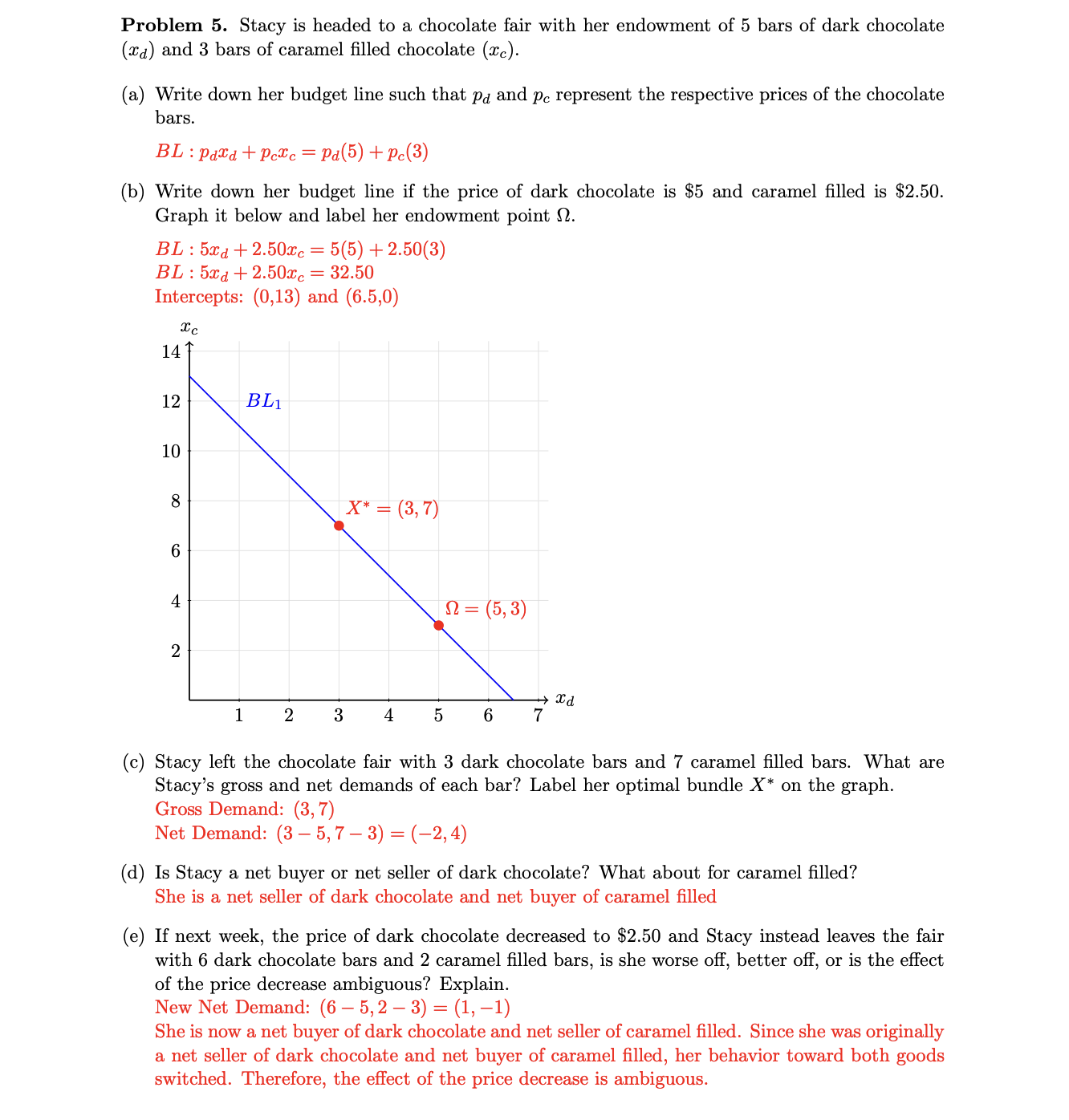

Principles of Microeconomics

Winter 2025 | Class Size: 56 | Mode: Online (Synchronous) Overall Rating: 4.2/5 | Full Course Evaluation Show Selected Comments ▼

- "I would recommend taking this course with this instructor because she is awesome and very passionate about microeconomics and teaching the course."

- "She was very clear with her explanations! Taught the topics extremely well!"

- "The course itself is challenging but the professor made it more fun to follow along in class."

Intermediate Microeconomics

Fall 2024 | Class Size: 140 | Mode: In-Person Overall Rating: 4.39/5 | Full Course Evaluation Show Selected Comments ▼

- "Sierra Smith was an excellent instructor and I learned a lot from this class!"

- "The problem sets/quizzes being a completion grade really took a lot of stress off my shoulders for a harder class. It allowed me to attempt the hws without the stress of getting everything right and rather helped me actually learn what I was doing."

- "Sierra Smith is a fantastic instructor. I cannot sing her praises enough. Class materials are of the highest quality. The quality of instruction provided is greater than excellent."

Spring 2024 | Class Size: 87 | Mode: In-Person Overall Rating: 4.55/5 | Full Course Evaluation Show Selected Comments ▼

- "Sierra Smith was a phenomenal GA that did a fantastic job of not only covering the material in a timely manner, but offering many opportunities for students to seek help outside of the lecture. I found Sierra to be a very quality instructor with an emphasis on ensuring that her students grasp materials and fully understand course concepts."

- "I thought not putting massive stress on quizzes and practice problem helped me learn better a lot. Sierra Smith did a great job at teaching the content, very satisfied with her teaching."

- "Sierra always made herself available and provided examples on anything we asked about."

Fall 2022 | Class Size: 75 | Mode: In-Person Overall Rating: 1.8/1 | Full Course Evaluation Show Selected Comments ▼

- "Everyone in the EC department had told me that EC301 was very difficult but Sierra made it one of my favorite Econ classes I have taken so far because she made it seem easy. She was easily one of the best Econ professors I have ever had and one of the best professors I have had in general in my 3 years at MSU"

- "I really enjoyed this course overall and learned a lot from the material. I think that Sierra was a great, effective instructor and I appreciated the amount of time and effort she put into teaching this course. I would recommend as an instructor her to anyone else who needs to take this course, and I would love to take other courses she would teach in the future."

- "I really enjoyed this class and the professor’s teaching style!! She was always willing to take questions and explain concepts until all students felt comfortable. It was my favorite class this semester!"

- "She is awesome. Cares about students and her work, and is receptive to feedback. Please keep people who are passionate about the work they do."

About Me

I'm an Economics Ph.D. candidate at Michigan State University

I’m a behavioral and experimental economist by day, and a hurricane-data-sleuth and Lego-specalist by… well, also by day.

My job market paper explores how reference dependence shapes flood insurance demand through hurricane forecast errors. I love teaching economics, especially when I

can bring data to life, spark a good debate, or sneak a behavioral experiment into the classroom. I live with two cats: Nash (yes, named after the economist)

and Lulu. I also have more than two houseplants. When I’m not in my office, you can find me basking in the sun, baking something sweet, reading something fun, or nursing a plant back to life.